A reason to be cheerful? By Claire Blakemore

There are many reasons I disagree with Toby Young, but one in particular is his reaction to the film I, Daniel Blake. The film, by Ken Loach, charts how a disabled man in his late fifties, out of work and with poor IT literacy tries to navigate his way through the benefits claims system, and finds himself caught up in an Orwellian bureaucratic nightmare. Toby Young was very upset. Not with the fundamental inhumanity of the Department for Work and Pensions claims system, or with the startling levels of poverty and inequality that have found themselves embedded in modern Britain. He was upset because he thought Loach had an: ‘absurdly romantic view of benefit claimants.’ He was upset because the benefit claimant wasn’t ‘drinking, smoking, gambling, or even watching television’. He was upset because Loach had the audacity to create a character that ‘listens to Radio 4, likes classical music and makes wooden toys for children’. [1] Toby Young was incandescent that a piece of art demonstrated that working class people were cultured.

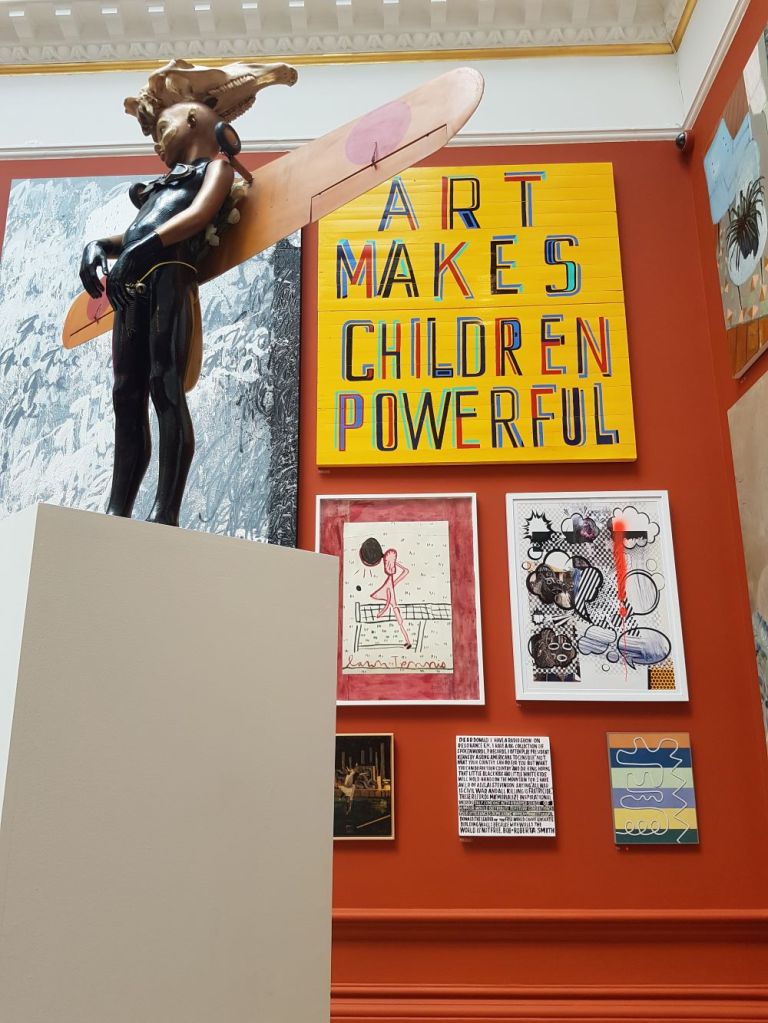

Figure 1Photo taken by Claire Blakemore Royal Academy Summe Exhibition 2017

That someone to the right of the political spectrum has this reaction isn’t much of a surprise. The last fourteen years of Conservative rule has been characterised by the strategic

de-prioritisation of the arts. In the state school curriculum art, dance, drama, literature and

music has been pushed aside in favour of science, technology, engineering and maths; leading to a startling 47% drop in students taking arts subjects at GCSE. [2] Funding in schools for these subjects is so bad, that Labour reported in 2022 that less than £10 is allocated per student for all music, arts, and cultural programmes. [3] The devaluing of the arts has been further compounded by local funding cuts that have reduced access to arts and cultural venues and spaces. In 2019/20, around 53.5 percent of 11-15 year olds in England were participating in theatre and drama activities, compared to 69 percent in year 2008/09. [4] The reality for too many young people is that they will never have visited a theatre, been to an art gallery, or museum to experience first hand the transformative power of art and culture.

The Cultural Learning Alliance calls this the learning enrichment gap, in 2017, a Sunday Times investigation found that private schools in London alone have 59 theatres.

between them, with many of them being state of the art. By contrast, the West End only has 42

theatres. [5] We spoke to local teachers in Havering, who say that the appetite for attending local theatres is as high as ever, and that many schools are still running trips and days out to the theatre, but that this effort is hampered by lack of funding. The number of places offered for students are limited, with demand vastly higher than places available. One of the biggest issues is the cost of staffing to replace the teachers that chaperone trips. Some teachers resort to using their own days off to minimise the staffing costs and make these trips happen. The teachers we spoke to said that to increase participation it would be great for theatre companies to visit the school themselves, or have more opportunities for artists in residence so that pupils see first hand what it means to be a professional creative. While there are some fantastic initiatives, for example Speak Up run by the National theatre, a lot depends on secure long-term funding for schools and local arts venues. Meanwhile, schools are increasingly losing art and drama teachers and the willingness and appetite for schools to provide access to these activities is precarious and too dependent on the goodwill of passionate teachers to keep them going. For example, if a drama teacher leaves, it can be the case that the provision of drama teaching will leave with it, given the subject is not on the national curriculum. Right now, the pressure on teachers is higher than ever, and with that, it is easier for cultural enrichment activities to fall down the list of priorities.

One of the consequences when we devalue the arts in state education is that we end up

with unequal representation in our creative industries. According to an analysis by

Labour nearly half of all British cultural stars nominated for major awards in the last decade

were educated at private schools. This is despite only 6% of the population being privately educated. [6] Meanwhile, the creative industries are suffering from a drought of diverse, imaginative creative talent. A report by Creative Access found that class is the missing dimension in diversity and inclusion in the creative industries, with 73% believing there is class-based discrimination, this is particularly pronounced in publishing. [7] While this is set to have an impact on our cultural heritage, health of our creative economy and international standing, another key dimension of denying children arts and culture is the impact on their mental health. A comprehensive study by Oxford researchers in 2023 found that young people’s mental health deteriorated during COVID-19, with higher levels of depression and social, emotional and behavioral difficulties than before the pandemic hit. [8] Arts and culture form part of a holistic package of education that ensures children feel a sense of connectedness to themselves, each other, and society. Art may not be a panacea for mental health, but allowing children the opportunity for artistic expression does form an important part of a broader education of the whole child.

But change, finally, is afoot. In March, Keir Starmer outlined Labour’s vision and long term strategy for the arts – putting creativity, art, and culture at the heart of their stated aim of a decade of national renewal. As Charlotte Higgins from the Guardian pointed out, the content of his speech mattered less than the fact that he was making it at all. [9] There has been a deafening silence for too long on the importance of the arts and culture to the UK, despite it being a fundamental component of our soft power as a nation, and as Starmer has pointed out, the bedrock of our ability to attract international investment – for example he noted Warner brothers building studios in the UK. In his speech, Starmer has promised to put creativity at the heart of the curriculum, ensuring that the school accountability framework is reworked to make sure that the arts count and that all children should study an arts or sports subject until 16. He also noted the importance of oracy skills being woven into the education system, something that private education already prides itself on. Encouragingly, there was also acknowledgement of the importance of the arts for health and wellbeing, noting that young people face a mental health crisis that the arts could go some way to mitigate. Starmer noted that while he ‘cannot turn on the taps’ in terms of funding straight away, the curriculum is something that is an immediate change that can be made. [10]

While the election is far from won, Keir Starmer’s speech was the first time anyone working in arts education has a reason to be hopeful in a long time. That we may, if all goes well, have someone in Downing Street who understands that the arts and economic vitality is not a zero sum game. That growing the economy and investing in the arts is not mutually exclusive. The stunted imagination evident in education policy in recent years has been worrying. When Rishi Sunak announced he wanted everyone to study maths to 18 it suggested there was no greater vision for education and skills other than educating everyone to become an investment banker like him. [11] This wouldn’t be so much of a problem if this announcement was complemented also by a focus on the arts, or it was joined up in some way with other elements of the curriculum, to provide young people a holistic education. It was a good example of policy being led by ego not evidence. Perhaps someone should tell Sunak about the link between mathematical and musical ability, and that studies show children who play musical instruments are able to complete complex mathematical problems better than peers who do not play instruments. [12]

Figure 2 Thangam Debbonaire MP Shadow Culture Secretary

Meanwhile, after 12 culture secretaries in 14 years, we now have the tantalising prospect of Thangam Debbonaire as a potential culture secretary. Debbonaire was a professional cellist who performed as part of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and describes her potential future post as her ‘dream job.’ If Debbonaire was elected, it would be a huge departure in and of itself, given that none of the last 12 cultural secretaries have had an arts education, the majority coming from Law or Finance backgrounds. [13] In a recent speech at Remix Summit London 2024, Debbonaire made another crucial point about the importance of arts and culture – the link with progress and emerging technologies, noting: ‘It is the creative industries that stimulate ideas of what another world could look like’. [14] Both Debbonaire and Starmer seem to fundamentally grasp that investment in arts and culture is what drives innovation, rather than distract from it. Crucially, both talk about creating the right conditions for art and culture to thrive, and that there has to be a holistic ecosystem, supported by many parts of society for people to not just take part in the arts, but take risks in it. Debbonaire has also underscored the need for diversity and equality to be part of building the right ecosystem, a critical dimension if we are to truly develop world-leading culture. She notes that she wants to see creative industries and art and culture, work together and that ‘the publicly invested sector feeds the commercial sector, and vice versa.’ [14] Critically for arts educators she wants every child to have access to high quality creative education, understanding that creativity skills are critical no matter what job a child may do in later life. But more than that, she understands that giving someone access to an outlet for creative expression is something that enriches a persons life, no matter who they are and what job they end up doing.

All these announcements are positive, but we have to be realistic that it will take decades of funding and hard work to try to undo some of the damage done over the last 14

years, and we are yet to fully see the impact of strangling arts investment on the next

generation of creative talent. But I want to end on a positive note, because if there is one thing

opening access to the arts gives us, it’s more optimism. Ken Loach announced his

retirement last year, but there are signs the next generation of filmmaking voices are

already here, in spite of the current political climate. The film, aptly titled Scrapper by Charlotte Regan depicts a young girl, who uses her wits to survive on her own terms after losing her mum. It recently won the World Cinema Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival. [15] Charlotte Regan, the director, identifies herself as working class, and has said that ‘I’d love to see more working-class films that are happier’. [16] The film is a joy, rather than the usual grey of kitchen sink, social realist drama it is colourful, fizzing with charm and eccentricity to reflect Charlotte’s lived experience. This is why people need to be able to express art in their own way. There is more to working class lives than poverty. There is humour, vitality, and community. As Reagan shows there are so many groundbreaking, entertaining stories still to be told.

Finally, as Starmer said in his speech, ‘talent doesn’t discriminate, opportunity does’. [10] Artistic talent, like sporting talent doesn’t care what’s in your bank balance. Labour’s job, if they are to win the next election is to ensure they do everything to make sure that finding that talent is not a lottery. They must build an ecosystem that not only finds creative talent, but nourishes it and helps it thrive. Not just because it is the right thing to do, but because when we allow the best artistic talent to shine, we give all of us the chance to see the world through new, more vivid, more optimistic eyes.

| Figure 3Claire Blakemore | Originally from Havering, Claire Blakemore is a freelance writer with over ten years’ experience in the communications industry. Having graduated with an MA in Creative Writing from Birkbeck in 2022, she has a particular interest in working class representation in storytelling and literature and is currently writing a series of essays about widening arts participation in the UK. |

++++

References:

- https://www.campaignforthearts.org/huge-decline-in-arts-subjects-worsens-at-gcse-and-a-level/

- https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/jul/15/creativity-crisis-looms-for-english-schools-due-to-arts-cuts-says-labour

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/421005/childrens-theatre-activities-engagement-england-uk-by-age/

- https://www.culturallearningalliance.org.uk/closing-the-enrichment-gap-between-independent-and-state-schools/#:~:text=In%202017%2C%20a%20Sunday%20Times,End%20only%20has%2042%20theatres.

- https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2024/mar/10/uk-award-nominees-privately-educated-labour-analysis#:~:text=Labour’s%20study%20mirrors%20the%20findings,of%20those%20who%20won%20Brits.

- https://creativeaccess.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/The-class-ceiling-in-the-creative-industries-report-2024-2.pdf

- https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2023-09-21-young-people-s-mental-health-deteriorated-greater-rate-during-pandemic-major-new

- https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/mar/15/labour-leader-arts-keir-starmer-background-culture

11. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-outlines-his-vision-for-maths-to-18

13. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secretary_of_State_for_Culture,_Media_and_Sport

16. https://www.bfi.org.uk/interviews/charlotte-regan-scrapper